Seth Jensen lay quietly on his back in the soft summer grass of Potts Field in Decatur, Illinois on a May afternoon of l908 watching the large white clouds move over him in a peace that passed his understanding but not his desire. They were like the giant thoughts of angels effortlessly unfolding, flowing into one another in never ending forms and shapes, separating and merging and changing without resistance or regret. Something about the clouds filled him with a glad calm, a dimly perceived hope. They seemed somehow perfect, quiet and slow and white and perfect. They were so different from the incessant storms that raced through his mind. “Where does it go wrong?” he thought. “Why can’t we just flow from experience to experience without such turbulence and discontent? Why couldn’t the hurried, confused pace of our lives be as clear and untroubled as the way the clouds moved? Why is there always this harsh striving? Maybe if I just watched the clouds every day for an hour I could learn.” He had never been able to understand why he was so different, why his feelings shifted and changed so violently and quickly like a small boat in a storm tossed sea. He could rise above the earth like a soaring eagle with a sense of limitless possibility and then without warning be plunged into quicksand, sinking into a hopeless stillness, hidden from any light.

His mind wandered back to his classroom. The endless raucous voices and the trivial chatter of the students, the constant bullying and senseless cruelty toward each other. It always saddened him, something about human nature had always seemed sad and mistaken to him. When he had started teaching math at the Decatur Grade school two years ago he had felt hopeful but this slowly drained away. He could never get them to listen. He could never get them to understand the wonderful importance of Math. They couldn’t see the perfection and purity, how uncomplicated it was, how it erased the confusion of life. They seemed unable to see it. They seemed to enjoy all the chaos of their lives, the tangled thoughts and turbulent emotions, the unending swell and cascade of events.

His thoughts drifted to his familiar strange flights of mind. How he would race about all week propelled by the excitement of a barely perceived joy as though a recess bell had been rung in the routine of life and all the earth was a beckoning playground causing an indescribable sweetness to bubble up inside him as if from some pool of occult happiness and the world would seem suddenly as richly colorful and varied as the glittering rubies, emeralds and pearls in pirates treasure. Even the loud, noisy students at school would appear different to him, like a fountain of energy and vitality flowing over.

Where before the hurried confusion and broken disarray of humanity had thrown him into continual sorrow and pain, he now began to see the rich dance and play of life as though it had been designed by some divine alchemy for limitless pleasure. He would walk for hours to drink in the diverse thrill of existence. Each street and house and vacant lot became a sharp adventure. He would see that each house was different with different people of different ages and faces and shapes, and that each had a different past and present and future seemed to him a miracle. How each morning they would all wake up and put on different socks and underwear and then have their separate breakfast and go through the day with different thoughts and impressions and sensations swirling and drifting through their minds like schools of fish. All this darted through his mind with a mixture of astonishment and joy.

Thoughts raced through him in an instant like a swift flood of light rays to be followed by another and another in endless succession bringing pleasure after pleasure like a carnival ride that wouldn’t stop or a woman that kept loving him and then the shelter of night would come with its sweet soft darkness and lead him to sleep where the mind would shower him with the strange mystery of dreams and when he awoke the events of his youth would rise up in vivid detail as if from a hidden chamber bringing with them a rich ecstatic aroma that carried the distilled essence of childhood in it. He could see crisply and clearly the thick black rubber pedals of his first fire-red tricycle and the cloudy calm thick drowsiness of Thanksgivings and could remember sharply, as though he were still there, his ache for Betty Heltzel at the eighth grade dance, the blue ribbon in her dark hair, the exact feel of the red apple in his brown sandwiched bag on the way to Couch School in the second grade where the October leaves lay scattered on the ground in crisp piles of brilliant reds and yellows among smooth shinny brown chestnuts.

All these impressions and images appeared to him in cascading flashes like a meteor shower bringing with them a view of life’s intoxicating richness that would lift him up and carry him along for days in an aerial buoyancy. Then suddenly, in an instant, he would descend back to earth and gray clouds would roll in on the sharp edges of his mind and his thoughts would become silent sharp arrows whose tips were soaked in poison.

Where before had been the freedom of open fields now swiftly, mysteriously an iron gate appeared before the world and the recess came to an abrupt end. Suddenly the dark sadness and terror of life would loom before him and the presence of death would accompany the falling of a leaf, a remembered joy, a bird passing overhead.

He would see people on the street, their lives rich and full of effortless ease while his seemed covered with a paralyzing net .He would see lovers holding hands and he would be filled with a sharp painful ache as though a deep longing would be forever denied him and he would gaze upon parents with their children and his life would appear pale and valueless. A black stillness would settle in his soul like a thief of life as though he had stepped off a curb into quicksand and everything his eyes would settle on would be filled with a gray horror of emptiness. He would hear the two people feeding ducks by the lake talking excitedly about the beautiful colors of the large males, see the duck’s quick colors, the sharp rainbow of their coats and he would feel nothing as though he were a stone statue unable to take it in yet unable to ignore it, as if the whole scene was taking place in another universe. There would seem no point in being in the world and everything would come to a stop in a barren land beyond desire, beyond the desire for desire, where even simple movement would require a painful effort beyond the reach of the will. He was never sure how long it lasted, hours, most of the day, or even into the next day for time itself became still and frozen and he would only feel a continual sharp unnamable pain of being buried while yet alive.

He would walk the same streets, past the houses which the day before had thrilled him with their hidden mysteries and rich stories and now see no point in their even being there, for their existence did not matter just as the young man and woman holding hands and talking eagerly to each other across the street did not matter. From his experience he knew there was nothing to be done about it. It was as absolute as death, impossible to resist and then unexpectedly he would happen to see a small bird lift off suddenly from the limb of a tree causing the limb to quiver and in that quivering there would be an incandescent flash like a tear in a hidden veil revealing the infinite endless joy of existence. He was never able to tell anyone about these states for when he attempted to find adequate words language would turn into a stone tool and render him mute.

Seth’s mind came back again to the clouds passing over him above Potts field. As he lay there looking up at them they seemed to be drifting and changing to an invisible timekeeper. He felt as if he was watching time, that time itself were flowing silently above him in a slow movement over the earth. He let himself drift up and mix into the soft mounds of brilliant whiteness until time itself disappeared pulling him into a procession without direction, freeing his thoughts of all weight and consequence so that his mind became effortless motion delivered from the endless insistence of intention or desire. In the eventless tranquility a frantic bird released itself from inside the cage of his body and he watched it soar up away from him into the clean white clouds and disappear. A part of him rose up and followed the bird into a soft cool vaporous mist of white cushions that filled him with a mixture of ecstasy and patience he’d never known. He tried to stay there but slowly felt the intrusive gravity of his body’s weight pulling him back into its chores. He continued to lie there a while not wanting to leave, then he got up reluctantly and left the park.

The next day Mr.Barret, the headmaster of his school, walked straight into his two o’clock math class without following the customary procedure of knocking. He just opened the door in a flurry and rushed in. There was a wild look in his usually dull eyes and his vest was unbuttoned. “My god,” he said “they did it, they’ve flown that damn machine. The news just came in from Kittyhawk. Sweet Jesus they flew in that machine, they got in it and rode in the air. They’re calling it an Air-Plane.” With that he abruptly turned and fled out the door and down the hall to Miss Wigmoor’s English class.

Seth felt something shift inside him that afternoon. It wasn’t just that he was stunned, it was something more. He sensed the possibility of something, something he couldn’t yet see clearly. A strange unnamable hope moved through him.

Several days later he was eating dinner in his small rooming house apartment when a line from Emily Dickinson appeared suddenly in his mind, ‘Hope, that thing with feathers that perches in the soul.’ “My god,” he thought “that’s it! It’s the clouds! The body of the soul had feathers now. It no longer needs to perch. It can fly, it can leave the earth and go up among the clouds.” He had a vision of the eagle soaring serene, self-sufficient and peaceful high above the earth. “It will change us,” he thought, “there will be an end to our confusion and cruelty.” He laughed out loud in his small apartment. The next day he hurried down to the telegraph office to pour over the few messages that had come in from Kittyhawk. Orville Wright! He marveled at seeing the actual name, that it was a real name belonging to a real person, the first person to leave the earth, to move in the air above the land. He lingered over every detail, what time he had left the ground, how far he had gone, how high and how fast.

Somehow after hearing of Kittyhawk the dark times became less frequent and he felt more confident about handling them. He spent the next few years following the progress of the air-plane. The first thing Saturday morning he would hurry down Sycamore Street to the dark maroon brick building of the Decatur Gazette to get a copy of the newspaper. Each flight reported would be higher and farther than the last and he would feel a renewed buoyancy rush through him. “Soon,” he thought, “soon.”

The last Sunday in February was cold and gray which accounted in part for the large turnout at Rev. Dillworth’s ten o’clock service. The other cause was the news of the air war in Europe. They were dropping bombs on cities and shooting at people from the new air-planes. The crowd that had gathered in front of the church busily exchanged opinions and rumors. Rev. Dillworth was in fact a little annoyed at the difficulty he had ushering the reluctant congregation into the church and was further dismayed when a young man in one of the last pews got up and left in the middle of his sermon.

The following Saturday morning Cleda Bishop finished washing the breakfast dishes, went outside and sat down on the porch steps where she could supervise the children’s chores and picked up the Gazette to scan the news. After a few minutes she dropped the paper on her lap and stared off into space, then said, “Sarah, where are you, come here.”

There was no answer and she raised her voice, “Sarah, do you hear me,? come here!” Sarah came walking slowly around the corner from the hen house with a large bucket of eggs in her hand. “Sarah, what’s the name of that math teacher of yours?” “Jensen,” she said with disinterest. “What’s his first name,” Cleda asked. “Seth, I think,” then firmly, “yes it’s Seth.” Cleda dropped the paper, “Well I’ll be damned, it’s him! They found him dead. Hanging from a rope in that old barn near the school. Why on earth would he do that?” “I don’t know,” Sarah said blankly, “Can I go now?” “Yes, you go on.” Sarah turned and walked back to the hen house with her eggs.

"Good taste is the death of art." Truman Capote

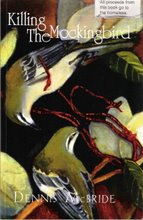

Check in at The Cirrhosis Motel with your host, freelance literary loiterer and epicure, Dennis McBride

photo by John Hogl

Sunday, June 17, 2007

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment