Even at an early age I realized that pleasure was serious, that it came way before the top ten of anything. When I was young pleasure was just unavoidable, it was everywhere, my head on my pillow, leaving the dentist’s office, watching a dog sleeping on a sidewalk in the sun, the golden brown syrup pouring onto my waffle. I think when we realize that the world means business we just complicate pleasure out of all possibility but a fugitive part of me always knew it was still here so even when I grew up I did not ‘put away the things of the child.’ Even a quick glance at the world of grown-ups told me they had nothing comparable to it.

It is strange how beginnings never seems to begin at the beginning, just the way things don’t really seem to happen till a while after they have happened. My beginning, or rather the tardy recollection of my tardy beginning ( since my real beginning, though mine, was denied to me, as to all of us ) began with the sight and smell of sea salal. All of my attention shrunk its focus to those thick, sharp, dark green, oddly lush bushes that surrounded the sidewalks of the small seaside town I found myself deposited in. Even my mother exists in their background. When ever I recall her I see salal. I don’t know where she is now, she’s been dead for some time.

That is, some time for me. For the dead I imagine it must be like you’ve always been dead, outside of time, which is why the peace passes understanding, all of life being so sudden and all.

It is strange also that I cannot remember my first memories though I know they’re there, my startling introduction to the world and then to me. They are buried in the labyrinth of the neuron’s synaptic maze. My earliest recollection is but the third or fourth car in the locomotive’s long torn trailer. It is there in those first few dim cars that the inscrutable instructions were laying down the narrow tracks on which I was to travel through the wide world, all the way to today, to two hours ago, when I buried the one I had lived with for eight years in my back yard next to the wood pile.

The reason I did that was not, of course, a reason at all, but the fugitive forces of those first forgotten filaments of being. I buried her for the simplest purpose, she was dead and I have an intrinsic disinterest in ceremony, not because, again, of some reason but because though the force of those ghostly filaments is forgotten, their form and frame remains, commanding, outside my intention, my every action. Perhaps free will is merely the somewhat delightful awareness of consciousness’ masquerading its action as choice.

I just forced the shovel into the ground and displaced the earth and then I did it again, and then again, until a grave, through the gradual disappearance of earth, appeared as cleverly as though it was the result of my complete, discreet action rather than a combination of unremembered influences which had accumulated as invisibly and effortlessly as lint.

I may get caught and have to explain from the beginning my ‘how’ and ‘why’ like God did in Genesis, and my answer will be as ultimately unsatisfying as God’s was, when, after all, the question is merely begged again. Philosophy, like prayer, may be one of the final expressions and confessions of human powerlessness but unlike prayer philosophy or explanations power is limited to the reach of understanding, the way a walk on a fishing pier is limited to the length of the pier.

I always hated having my beeper paged on the way to the cafeteria when I was in the Hospital. That day I was particularly hungry and the ‘Jesus Christ’ that slipped out of me at the sound of my beeper was louder than usual drawing disapproving glances from two nurses walking down the hall twenty feet in front of me. “Respiratory call 3 south intensive care 311.” I stopped at a wall phone outside the cafeteria and dialed. Susan King the para-military marine cleverly disguised as an ICU charge nurse commanded in language cleverly disguised as a request that I come right away and look at the young girl in bed 2 who had been coughing up a little blood from her tracheostomy. It was queen to drone. I hung up the phone and headed to three south.

When I arrived I pulled her chart. She was a 19 year old MVA who had been transported from the Dalles two days ago for multiple internal injuries. They had done a spleenectomy yesterday and she’d had an unremarkable post op course and was expected to recover nicely. Home Health was already working on her discharge which was planned for the end of the week. I saw that she had had a bronchoscopy in the morning and told the nurses that the bleeding was probably secondary to that. I called her attending, Dr. Elsin and told him. He agreed but asked me to change her trach as they has put on of the old metal ‘Morsch’ tubes in her at the Dalles. We agreed on trying a number 8 Portex.

I went into her bedside. Her mother was sitting in a chair beside her knitting. I told them that I was going to put in a newer trach tube that would be much more comfortable.

Her mother rose and set her knitting down in the chair. She said she was ready for a stretch and would go down to the cafeteria for a quick bite. She looked at me, “How long a bite should I take.” “About 15 minutes including dessert,” I said. She gave a squeeze of her daughters foot at she passed the foot of the bed and pointed at her knitting, “Watch my masterpiece,” she said and sauntered out.

I went and got the trach tray and laid it out on the bedside table. “You looking forward to getting back to the Dalles,” I asked. She nodded with a glad look and flashed me a thumbs up alongside a slight look of nervous apprehension. “You’ll like this tube a lot better, you can talk with it.” I said. She raised her eyes in a delighted smile.

I raised the head of her bed to about 35 degrees. “This will be real quick but it might make you cough a little when I put it in.” I said, “I'll just cut that string around your neck and its ‘out with the old, in with the new.’ She gave a small anxious ‘what ever’ sigh with her eyes then reached for her pad and pencil and wrote, ‘cliche's make me cough.’

I laughed and cut the string. “Okay, I'm just going to put this suction catheter down for a quick vacuums job and bring them both out together” I said casually.

The suction catheter caused a strong spasmodic coughing spell. I pulled the trach tube out quickly and had the new one half way in when a sudden force of blood flooded through it and around it. I put the suction on ‘high’ but it just kept coming in larger pulsating streams. My stomach tightened as the small alarm in my mind started going off. I noticed her eyes quizzically monitoring mine for signs of an ‘it’s nothing to worry about' reassurance. A sudden gusher of bright red blood forced the new trach tube out onto her gown. I tried to put it back but with the steady pulsating gushers of projectile blood I couldn’t even see where the surgical stoma opening in her throat was then finally forced it in with a frantic thrust.

The suction couldn't keep up with the rush of her blood. I avoided her eyes which had moved from a trust in me, in my white coat, in the Hospital, to a small sudden suspicion of ‘something wrong’ then to an involuntary animal fear. The terrorizing thought ‘artery’ turned the knot in my stomach into cement. I kept inflating more air in the cuff of the trach tube but it didn’t even slow the rapid increase of rushing blood. I yelled out “Nurse, I need help now!” and two came running in, “Get another suction and get the house surgeon here stat.” I turned my head back to her again. The blood was flowing slowly out of her nose and ears and the corners of her eyes. I froze. We locked eyes for an instant, an accident, the panic in mine delivering a terrifying knowledge to her and through her back again to me, a knowing beyond comprehension yet somewhere within it.

That was the last time I looked at her. I never saw her again. The surgeon arrived. I left. I went into the break room behind the unit and sat down on something. The surgeon pronounced her in three minutes. He came back to me and put a hand on my shoulder, “Innominate artery, nobody could have done anything. I’m on call all night, you need to talk, come to me, you understand !”

Fear. That was all I felt. Just fear for almost the whole month afterwards. I forgot about the Mother. I didn’t even remember her for several years. Now she’s there in the oddest places, at street intersections when I’m waiting for a red light, or in the dentist chair, or stepping into the bath, or raising a fork to my mouth. I can’t remember her daughter’s face. Not at all. I thought for a while it was because we were really just strangers but then so was her mother and I can see her as clear now as if she were sitting in front of me knitting.

"Good taste is the death of art." Truman Capote

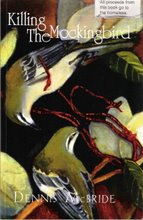

Check in at The Cirrhosis Motel with your host, freelance literary loiterer and epicure, Dennis McBride

photo by John Hogl

Sunday, July 1, 2007

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment