"Good taste is the death of art." Truman Capote

Check in at The Cirrhosis Motel with your host, freelance literary loiterer and epicure, Dennis McBride

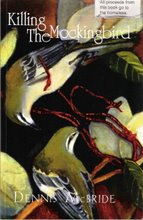

photo by John Hogl

Monday, April 11, 2011

American Suicide: A Story Problem You have multiple problems as you approach middle age: crippling arthritis, an artificial hip that confines you to a wheelchair, you have a history of clinical depression, you are laid off your job at Meier & Frank (a Portland department store) after eighteen years due to downsizing cutbacks; you can only find temporary jobs that do not provide health insurance so your savings are drained to pay for health care and prescribed medication. You are living in continual exhaustion. You are being evicted. Your van is being repossessed, and you file for bankruptcy. But you are a resourceful, independent person surrounded by wonderful support from family and friends. Solution: A week after having your role celebrated as a contributory family member at Thanksgiving dinner, you “choose” to kill yourself. There is a suicide every 17 minutes in the United States.* This suicide statistic entered my awareness around the time I happened to run across an article on a local suicide in our state’s most prominent newspaper, The Oregonian. The treatment in the article’s coverage rang some immediate alarm bells for me. It seemed to lack an expected measure of journalistic inquiry in addition to containing some rather questionable assumptions, and I found myself prompted to read it again with more focused attention. William Temple once accurately observed that “unless all of existence is a medium of revelation, no revelation is possible.” This essay is my attempt to reveal that, despite the passage of time since the story was originally published, what happened to one women’s life was not irrelevant, but deeply revelatory, and its resurrection is an attempt to illustrate its importance for us; to slow down, contemplate and even arrest briefly the accelerating speed of our own transience, the insistent gathering weight of our own irrelevance. Imagination is our fundamental moral faculty. It is central to grasping the nature and meaning of a significant event. The American poet Richard Hugo pointed out, “our great failure is our inability to imagine the suffering of others.” These reflections are dedicated to the real people who every 17 minutes make their premature departure. This was the headline on Nicki Dyer’s suicide in the Sunday Oregonian in December 2004: “Independent to the end. In pain and jobless, but refusing to lean on family and friends, Nicki Dyer chooses death.” The headline had all the qualities of a star-spangled American anthem, including the stoic oath of silence. All it lacked was musical accompaniment. The article presented us with a real trooper, with her “dignified resignation” and “self-reliance” who finally “chose” the stiff upper lip of death. Something seemed buried above ground in this tragedy. The article would have you believe that self-reliance and pride in the self is expressed in choosing to kill yourself, that independence of spirit is manifested as suicide, that somehow it was her strength of character that destroyed her. With such strength, who needs weakness?! When choice is examined more closely it becomes complex. To choose freely is far different than to choose under duress, negating what the spirit of the definition of choice implies. Do we choose what we’re going to choose? Choice is more a concept than a fact, and a fuzzy one at that. You draw your bath water to a temperature that is comfortable to you, not to one you chose to want. We are not radically free, after all. In addition the term choice is too often used to dignify where we have landed, or to blame others for where they have landed, as a tool for manufacturing a plausible and rewarding narrative about reality, life, self, and our place in the universe. This helps us to lessen and tolerate the insecurity and chaos of life, avoiding awareness of the variety of trap doors we’re all standing on. The disturbing questions move in like an ominous weather front hanging over everything about Nicki’s story, but the largest and loudest is the absence of anger over what was happening to her. Where is the outrage, the indignation from those who knew and loved her? It is not the overall absence of any trace of justifiable rage in the Oregonian article, but chillingly, even from Nicki herself (excluding a single emotional outburst at work). Why was everyone consenting to what was happening to her? According to the article, Nicki Dyer possessed the character traits of independence, self-reliance and pride, while also surrounded by a wealth of supportive family and friends. These are the ingredients for buoyant optimism—a recipe for having a nice day and a nice life to boot—not for suicide. In fact, Nicki’s suicide seemed a non sequitur. The article was not covering a minor problem like her failure to adapt to a style of living different from the one she was accustomed to. The hidden truth was that Nicki Dyer dissolved in plain sight, in front of everyone she was close to. Pride is about what you value, what you want to display. Suicide is the polar opposite of pride; it is default control; the individual’s powers being inadequate or insufficient to meet one’s own needs. It is about the soul not receiving its due. The article’s illogical treatment of Nicki’s painful story described a matter/antimatter do-se-do square dance of tragedy, pushing the limits of common sense into a gradual tsunami of reason gone mad, turning the crucial accuracy of language into a crude stone tool. Isn’t the purpose in all of our “purpose-driven” lives to be alive, to live? Worse, as disturbing as the article’s spin was on this particular suicide, having it go unchallenged in the largest newspaper in the state of Oregon—was even more so. The truth is that as far as pride and self-worth are concerned, we’re all hard-wired to avoid the rejection of losing face, of not living up to the standards of those who have the power to withhold love and caring, or to affect self-esteem. No one’s comfort zone extends too far beyond a sense of personal safety. Ultimately we’re all wimps. No one climbs Everest naked, and pride and independence can serve as barricades against fear, failure, complexity, despair and death, just as suicide can. The place where we are most equal is in our fundamental powerlessness. In his book The Soul’s Code, James Hillman observed that “The very ground of relationship is dependence, not independence; it is the very ground and motive for what authentic relationship requires.” Contrary to the article’s headline, “independent to the end,” Nicki was dependent on a necessary measure of comfort and safety, a sanctuary that enables us to feel that life is worth living. She was surrounded by support that was, in reality, inadequate or insufficient to meet a need that all her independent determination and self-reliance was also unable to provide. In fact she was dependent to the end—on someone to actually get the message that she was in real trouble. The irony is that we’re all dependent to a significant extent on others for our autonomy and independence. We tend to think that we are the sole authors of our thoughts, opinions, ideas and feelings; that they come out of a “nowhere” somewhere inside us, emerging by magic from a “self.” But the facts of reality are that feelings—like the impulse to commit suicide, or the complex forces underlying individual “character”—do not happen in a vacuum, but are produced out of the context of a large, webbed network of relationships, comprised of one’s biology, personal history, family, friends, community, race, country and culture. We have less control over who we are and how we think of ourselves than we think we do. Underlying all ethics and morality is the sense that we matter, that what happens to you as an individual matters and that leads, by some hidden mechanism, to a truth in the head and heart that others also matter. We send messages to each other all the time even if we don’t want to or aren’t aware of it, and much of how we value ourselves comes from the messages we receive from friends, family, community and country. What is ultimately allowed to happen to us can be one of the strongest messages conveying if and how much we matter, often driving us to insist too strenuously that we do matter, sometimes with too much distorted “pride” or “independence.” Nicki couldn’t afford health insurance. The deeper irony is that no one really needs health insurance. All we really need is health care. She was given the message that her health and welfare were not of intrinsic, irreplaceable value, a message coming from a culture and community currently existing in a human ethical coma. It is easy to understand how society’s recruiting officer for self-reliance and independence is so successful when there is such a deep and legitimate desire for independence in all of us. Who doesn’t want to lace their own shoes, butter their own bread? It is easy then to make the leap to thinking we are, or certainly should be, in command of our own fate. We completely buy into such an untenable position even when it is obvious that the three wolves of nurture, nature and economics—whose formidable powers are ultimately beyond the control of the individual—can huff and puff and blow our coherent, orderly straw houses down, a fact that should, by itself, call our simplistic beliefs of choice and independence into question. Such facile concepts are not just a leap of faith, but a leap of ignorance. One of our most important critical faculties—maybe our most important—is the ability to distinguish between what is inadequate and what is sufficient, and suicide points to a profound absence of hope. What if the source of hope and optimism is limited to oneself, and one’s resources the only really acceptable place to seek it? Imagine carrying such an overwhelming burden of hopelessness and pressure in your psychic backpack that you wanted to end your life—and then not being able to fully reveal it to those closest to you? Nicki’s refusal to grasp the ropes or lifelines thrown to her begs the question: why did she not reach for and grab them? The words choice and independence do not supply an answer, but instead point back to the question: what was really offered at those private exchanges between family and friends, and in the context of what personal histories between the participants? What were the lifelines that were actually thrown to her, were they within her ability to grasp, were they insubstantial or thrown too late? We seldom jeopardize our own survival. After all, the Titanic’s survivors rowed away from the people in the water, not toward them. But aside from that, there are excellent reasons for being hesitant to ask for aid. To reach out and really ask for help is to call enemy fire to your position. To even consider being deserving is to invite a direct hit of that criticism, of the shame and fear that is reserved for anyone with the inevitable scarlet “V” on their breast: anyone viewed as a victim or who has failed the self-reliance test. And this despite the truth that Nicki had contributed to the best of her ability. Nicki’s story contains not only a heroic display of individual determination, but also an indictment of an invisible virus in our culture that seems intent on encouraging self-destruction in order to salvage an acceptable sense of self. In such a culture, our innate need for a sense of our own independence and self-reliance is turned against us, creating a painful, isolated reality others cannot or will not acknowledge or even care about, and where we must endure and face far too many challenging situations and conflicts in solitude. Serious research is revealing how our emotional states impact the way our brains process information; we think differently under the sway of different mood states. It is easy to imagine how it could take far less than the significant sustained stress that Nicki endured for life to change from a promise to a threat, to make one lose the small degree of actual freedom and self-sufficiency that we do possess, to feel there’s no place outside of the “independent” self to really turn to. It is beyond the farthest reaches of reason to assume Nicki was feeling anything other than emotionally feral; buried alive on the day of her death, or even the weeks (months, years?) leading up to it. We don’t think so much as we feel, and to live without an income adequate to provide basic, vital human needs is to live in a continual urgent emergency that over time becomes a form of drip-torture. By casually suggesting that Nicki “chose” suicide the article assumes a degree of autonomy that is unrealistic for someone experiencing her pressures and circumstances. Suicide usually reflects (excluding the legitimate assisted suicide issue) the opposite of choice, the absence of alternatives. The act’s awful power is that you don’t go to it, it comes to you. When we cannot adequately respond to an assault on our dignity, our failure deepens the indignity and indignation. Instead of feeling free to respond with honest feelings of fear or frustration or even anger, it is easy to understand Nicki feeling compelled to show gratitude, to acknowledge a gesture’s thoughtfulness rather than its inadequacy. If we put ourselves in Nicki’s place, we can see how difficult, if not impossible, it would be to permit herself to even feel anger—much less voice it—to those who were always there at the edge of the swamp with condolences and praise for her “independence;” those whose version of support was well-intentioned and consistent with the forms we are taught to recognize as representing support. It is hard to scream, “where is the lifeline?” even when it seems obvious that, neck-deep in quicksand, support has no right to appear in any other form but a lifeline. All of this is not even to mention the hidden anger one harbors for being forced to turn the arrow of blame back at oneself. Neither Poe nor Kafka could have devised a torture as clever and subtle as having the victims of cruel circumstances victimize themselves by accepting entire responsibility. It is unfortunate that anger has become so suspect in our age of “anger management.” There is much interest and counseling on how to control and dampen anger, how to disarm it, detour it, talk it away, reason it away, educate, meditate, pray, love, or medicate it away—even gene therapy or taser it away—anything but how to listen to it, much less validate it. And what is the “red badge” of self-reliance, anyway? What is it about “unable” and “disabled” we feel so compelled to disgrace, to reserve for the cellar of shame? We all have limits in a surplus of varieties—psychological, emotional, social, sexual and financial—so why do we insist on avoiding them, as though the human spirit is somehow excluded from functioning within anything resembling limits? There are many ways I could justify and rationalize the Oregonian article's point of view on Nicki Dyer’ suicide, but I can't accept or excuse it, or give it my consent. It is too important to be framed in the lame plea of the “serenity prayer” for help in accepting those things we cannot change, or to be viewed in the sanitary pastime of a moral debate, or as an ethical or political lapse of judgment where it can sneak in under the radar clothed in the respectable convention of traditional values, which do not trigger the mind’s defenses or draw the gasps of shock or horror that tanks or teargas or terrorist’s bombs would. For me or anyone to sanction this article’s spin gives a pass to a laziness of sympathetic imagination that impairs our humanity. The thinly veiled hysteria that surrounds our love of “independence” and “self-reliance” is fool’s gold viewed through a carnival mirror, a deadly recipe whose ingredients would only be chosen if one were coerced by harsh circumstance and the absence of authentic support alternatives. There are cruel illusions involved in overestimating the degree of control we have over our lives, while ignoring and discouraging any examination of the overall systems in which we live our lives, those forces outside of our control. The Oregonian's article inadvertently evokes comparisons with Rachael Carson's classic “Silent Spring” or even Jack Finney's “Invasion of The Body Snatchers” by illuminating the slow but growing erosion of that elusive something which is central to what it means to be a human being. Without that we lose the ability to allow what is most vital about us to play a role in how we perceive and treat one another; we lose touch with those things that make our individual and collective importance possible, like the relative measure of comfort and safety we require to feel life is worth living. By itself, Nicki’s death asks the question of whether there really is a social contract that exists outside the criminal justice system, that covers the welfare of the village inhabitants, or does it respond only to those suspected of misbehaving? Community of meaningful connection is only possible when we can openly share our lives with safety, when we can protect the intimacies and fragile security which we are genetically driven to need. When we can’t it increases our separation as well as our anxiety, mistrust and suspicion. The pendulum that swings in our lives between independence and dependence is regulated by a sense of trust, in feeling comfortable and confident that our own efforts can be effective in meeting our needs, and should we fail, that others can be relied upon to assist with or help provide for our needs, to preserve the integrity of the self. We live in a country and culture where the pendulum is stuck, rusted into a dangerously unrealistic position of self-reliance that socially engineers tragedy. It doesn’t take a global positioning satellite to locate the dead end of Nicki’s life. She was a victim of repeated doses of devastating bad luck and crucial disappointments. How was she to believe she had innate worth and value outside the proud, reinforced confines of her own mind, to feel she was more than a human hubcap, when all the efforts of her life’s checks were returned for “insufficient funds”? To try to rationalize and explain away her tragedy is to explain away our own humanity. If we can advance the concept of death with dignity, why shouldn't we begin to explore the complex of tangibles and intangibles that constitute life with dignity? We have become a warp drive, super speed, digital culture of high tech rationalists and realists whose batteries are too weak to show us the way, to illuminate the surrounding dark.. This is not just about a “political” position we can “agree to disagree” on. If we cannot find our way out of this dark empty box, we’re all going to die inside it. It really doesn’t matter what flag you wave or what anthem you sing. If the critical needs of the people in a country don’t come first, the needs of the country do not deserve consideration. They are not worth even a backward glance. This tragedy is not only about the fate of Nicki Dyer but about an abandonment which is systematically woven into the fabric of a culture that has surrendered the idea of anyone being of intrinsic and irreplaceable value. A human being, an American, one of us was destroyed through acts of omission and commission, in a culture we are creating. Her story demands and deserves to be looked at closely because it points back to the heart of our culture, the health of our social values, our way of life as “the greatest nation on earth.” It is not just another story of someone falling through the cracks, failed by the system. It is a story of an individual’s free fall through the system itself, in the quicksand of the public sector as well as the private sector, a landscape with no human sector, revealing it to be one big, wide-open abyss, waiting for anyone.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

1 comment:

required reading - thanks for writing this and putting it up, dennis.

Post a Comment